Twinkies at Dawn

When you travel for photography, you don’t live by time — you live by light, which is how Anne and I wound up at the Qwiki Mart in Beatty before sunrise, arming ourselves with coffee, Twinkies, and HoHos for the long road north.

Back in the car, Anne immediately staked her claim on both cupholders. Her giant metal water mug went in the forward slot, which also happens to block the shifter. When I tried to put the car in drive, the lever jammed against stainless steel. Without a word, she swapped things around, wedging her Diet Coke and its koozie in it. I glanced at my steaming coffee. Anne just snorted, “It’s my car.” Which is how I wound up driving north with a hot cup balanced between my bare knees.

Only then, as dawn began to creep into the sky, did we pass the neon glow of an open Denny’s — real eggs and pancakes mocking us as we rattled by on our breakfast of champions—road-trip cuisine in its lowest register: no bass, no treble, just sugar noise.

Riding the Frozen Waves

North of Beatty, US-93 begins its slow transformation into Interstate 11. Some stretches are still two-lane blacktop, others widen into a broad, empty four-lane highway. The land doesn’t soar like the Rockies. Instead, the road undulates through a rhythm of long troughs and low crests.

Driving it feels less like climbing mountains and more like riding a surfboard across a frozen sea — the waves don’t move, but you do, sliding over sage-filled valleys and ridges that rise like still swells.

Each crest has its own name — the San Antonio Mountains, the Weepah Hills, and a string of other north–south ranges that march up Nevada like ribs on a washboard. The basins between are carpeted with sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and bunch grass, muted greens and tans broken only by the occasional black ribbon of lava flow. Even in the still morning, the silence has weight.

Somewhere over the Weepah Hills, I heard a low rumble. Not thunder — Anne’s stomach, reminding me that Twinkies and HoHos don’t qualify as breakfast. I promised her “real food in Goldfield,” but the look she gave me said I was running out of goodwill.

Geologists explain this landscape as the dented fender of North America — stretched and buckled when the Pacific Plate shoved against the continent. Faults cracked open, magma rose, and ancient water moved through the fractures. As it cooled, it dropped its load of dissolved minerals in stripes and pockets along the ranges. That hidden plumbing left behind a string of boomtowns almost in a line:

-

- Virginia City (1859): The Comstock Lode, one of the richest silver strikes in history, swelled to 25,000 people.

- Tonopah (1900): Silver again, Nevada’s leading district at the time, with 10,000 residents.

- Goldfield (1902): High-grade gold, enough to briefly make it Nevada’s largest city, population 20,000.

- Rhyolite (1904): A flash-in-the-pan gold camp, 5,000 souls at its peak, abandoned within a decade.

Like waves on that frozen sea, the booms got smaller with each crest. The land gave up its biggest fortunes first; later strikes were shorter rides.

You can see it in how the towns aged:

-

- Virginia City survives not just as a tourist stop, but as the tourist stop that Jerome, Bisbee, and even Oatman would hope to be when they grew up—boardwalks, saloons, museums, and a main street that feels alive.

- Tonopah remains a regional hub, boasting hot water both underground and in the hotel showers.

- Goldfield is like an old man with missing teeth — fine buildings still standing, but plenty of gaps in the smile. Like a half-finished chord, you strain to imagine what the complete harmony must have sounded like.

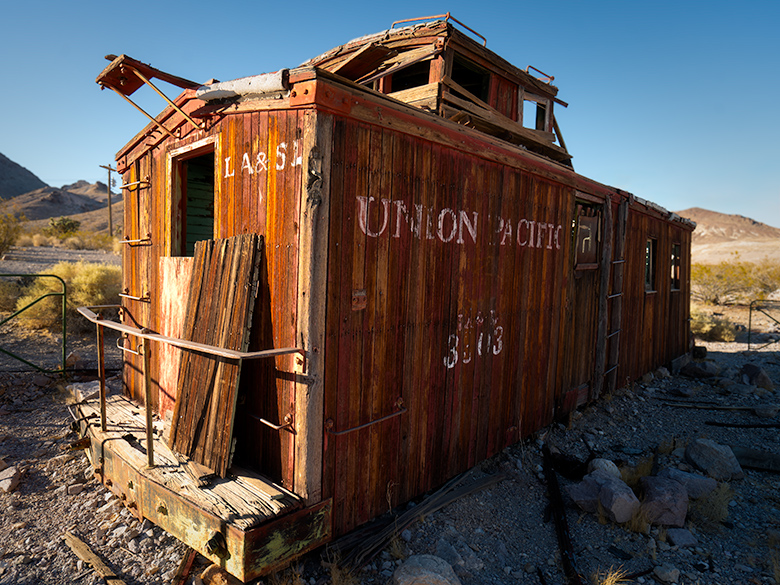

- Rhyolite is the geezer with a single tooth, the Cook Bank ruin grinning lonesome in the desert sun.

It looks barren now — just sage, stone, and the echo of Anne’s stomach growling — but the bones of this desert still hum with the story of fortunes found and lost.

The Mizpah Mirage

Across another basin, and over the far side of the San Antonio Range, we rolled into Tonopah — Anne already scanning for a swanky place to eat, finally. We didn’t need gas; we’d topped off back in Beatty along with our Twinkies and HoHos. But Reno was still a long way up the road, and we both knew gas only got pricier the farther north you went. So as we cruised through town, we couldn’t help noticing every marquee: to the penny, the same price at every station. The only outlier was Chevron, which was precisely a dime higher. It felt less like competition and more like a cartel.

Since Anne had been so patient — running on HoHos, a Diet Coke, and stomach growls — I promised her something swanky. “We’ll find a place with Eggs Benedict,” I said. “Maybe some savory crêpes, or even a croque monsieur if we’re lucky.”

That’s when we spotted the Mizpah Hotel, its grand façade rising like a mirage. A sign promised breakfast in the Jack Dempsey Room. Perfect. The Mizpah had history, glamour, and a name you could drop at dinner parties. This was the spot. “Come on,” I told Anne. “My treat,” like there was ever another choice.

We walked in expecting linen napkins, chandeliers, and maybe a ghost in the corner for atmosphere. What we got was Comfort Inn dressed in vintage wallpaper. The buffet line offered the usual suspects: dry potato cubes masquerading as hash browns, biscuits drowning in red-eye gravy, and pre-formed egg rounds that looked like they’d been cut with a hole saw. Worst of all, not even a waffle maker.

Anne stared at her plate, then at me. Her silence was louder than words, and the message was clear: you promised Eggs Benedict, and I got yellow hockey pucks.

The room itself was lovely, more like a museum piece than a hotel dining room. Period wallpaper, patterned carpet, chandeliers overhead, and portraits on the walls in oval frames — the kind my parents had one of me in as an infant (I think my sister still has it). Sunlight filtered through lace curtains, softening the edges of disappointment on our plates.

After eating, we took turns freshening up for the long road ahead. Anne disappeared down the hallway and was gone long enough that I thought the ghost had abducted her. When she came back, she explained that the corridor walls were lined with photos of visiting celebrities — and of course, she had to stop and name every one of them.

By the time we walked back out to the car, there was still grumbling, but this time it wasn’t Anne’s stomach.

Mean Grandma

We didn’t really need gas. The Corolla still had plenty left from Beatty, but Reno was a long way away, and up here, you never knew what the next price jump would be. So I pulled into the last station at the edge of Tonopah, figuring I’d top off just in case.

The tank filled, but when I pressed the button for a receipt, the screen flashed back: See cashier inside. Around the side, a Coke truck was making its delivery. The driver had propped the door open, and since I didn’t feel like walking all the way around the front, I slipped in with the sodas.

Behind the counter was a woman so thin, with lines etched so deeply into her face and hands, that she looked as though she could have been around during Tonopah’s original boom. Maybe she was working because help is scarce these days, or perhaps she just wanted a little extra money for the slot machines. Either way, she stood behind the register with the quiet dignity of someone who had seen a lot more desert mornings than I had.

She printed my receipt and handed it over without a word. Business done, I turned toward the open delivery door.

“Not that way,” she barked suddenly. “Deliveries only.”

I froze, receipt in hand. “What are you going to do?” I stammered, “Call the cops and have me arrested for using the wrong door?”

Her eyes narrowed. Without rushing, she reached under the counter and began pulling out the longest silver revolver I’d ever seen outside of a Clint Eastwood movie. “Go ahead, punk,” she said, voice steady as bedrock. “Make my day.”

My jaw dropped. Whatever clever comeback I thought I had withered into a croak. I stuttered something unintelligible, stuffed the receipt in my pocket, and spun on my heels.

Out the front door I went, tail tucked between my legs, half-expecting the barrel to follow me through the glass. I bolted into the Corolla like a kid sneaking past curfew, and Anne barely had time to ask what took so long before I mashed the pedal.

We launched over the curb with a squeal of tires and a set of skid marks that Marisa Tomei herself would’ve had to explain in court. I didn’t breathe again until the Tonopah city limits were in the rearview.

Finally, a Real Nevada Payoff

Out on Nevada’s backroads, nothing goes quite the way you plan. Golden hour fades too fast, boomtowns turn to ruins, and “fine dining” can mean egg rounds and potato cubes. But in between, you get shadows that linger just long enough for a photograph, the stubborn charm of towns with missing teeth, and stories you couldn’t invent if you tried. That’s the real payoff—the light, the laughter, and the long road north.

Till next time, keep your humor dry and brush those pearly whites.

jw