Thanks for tuning in to the third installment of my tromp through Prescott’s Granite Dells. We’ve moved to the park’s west side this week, north of Wilson Lake, where the trails are more challenging (physically and mentally) for an old coot like me. Despite the park departments placing white dots along the route as breadcrumbs, this Hansel managed to get lost three times. When I wasn’t lost, I scrambled over rocks and through thickets. To add to my misery, I started my hike in the afternoon, when the temperature was hot—even for Prescott.

Ah, the granite of Arizona, often found lounging in the sun, unbothered and with a certain rough charm. Unlike its posh cousin in Yosemite, it’s not entirely dressed to impress. While the Yosemite granite is a refined mix of quartz, feldspar, and biotite, giving it a smooth, elite look, Arizona’s granite is laid-back.

Arizona’s granite likes to hang out with some low-life friends, like mica and other composite minerals. It’s a mixed bag of characters not found in the high-end stuff. It’s a bit like the rebellious teenager of the geological world, not entirely fitting into the pristine and orderly world of Yosemite’s elite granite or New Hampshire’s distinguished, old-world charm.

Where other granites may be used for grand monuments or chic interior design, Arizona’s granite prefers the simpler life—gracing landscapes, lounging in gardens, or even being crushed into gravel for driveways. The added presence of mica gives it a bit of sparkle, but it’s more of a casual glint rather than a dazzling shimmer. It may not have the star power of its Yosemite counterpart, but it’s got character, grit, and a unique Southwestern flair that makes it stand out in its own right. And who doesn’t love a good underdog story? Especially one with a bit of sparkle!

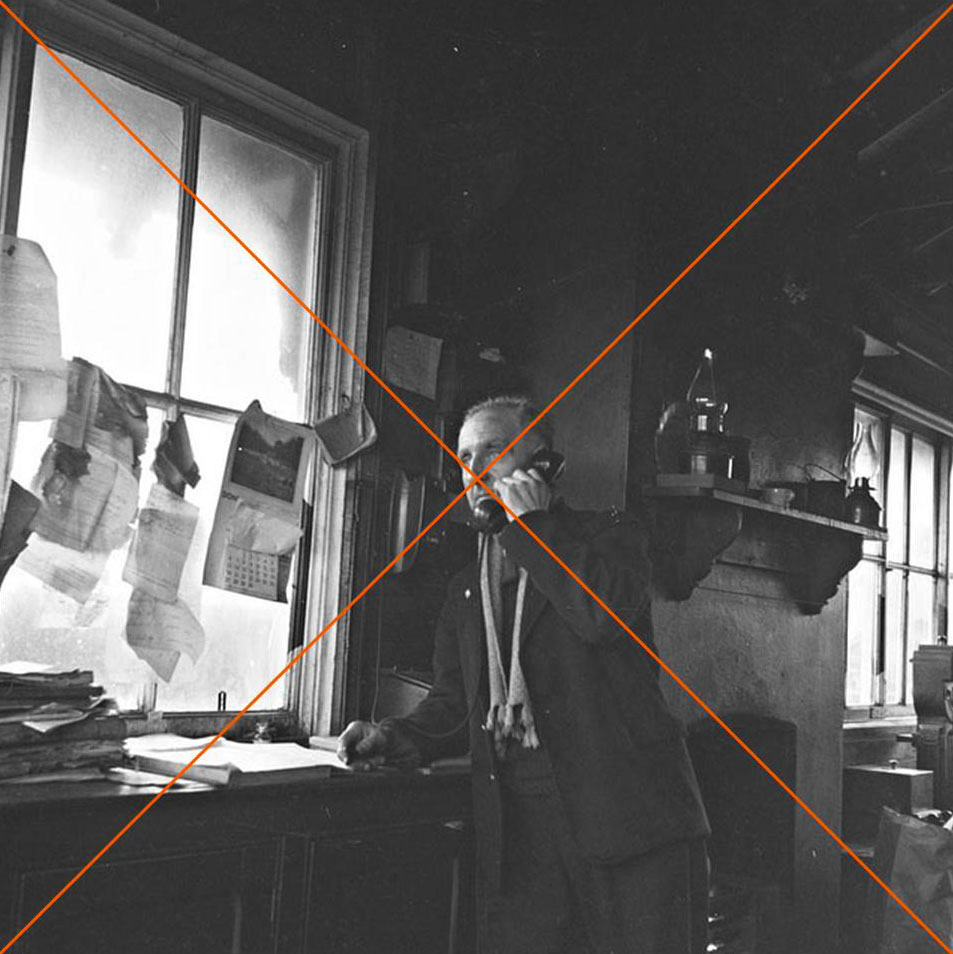

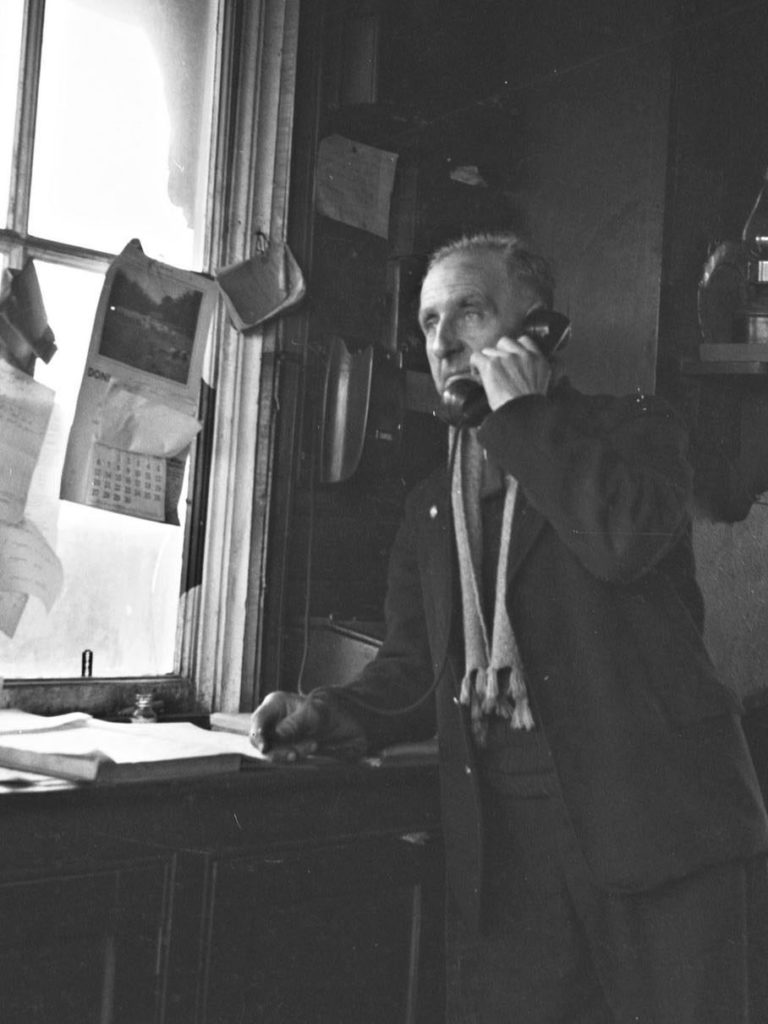

When hunting down picture subjects, I look for unusual things that interest me. It may be a pattern, shape, texture, or something ordinary, but with exceptional lighting, photography loosely translates to ‘painting with light.’ But when I try to explain to others what I see in an image, my audience frequently gives strange looks, and they often raise their hands in defense before taking a step back for safety. For example, I was drawn to the inclining row of vertical rocks behind some horizontal slabs in this week’s image, titled The Escalator Effect: Rock Formations in the Granite Dells. My brain shouted, “Oooh! Oooh! Rock go up and down—rock go side to side.” That was enough encouragement for me to snap the shutter.

The composition still pleased me enough to process it this week, but as I worked on it, I began seeing things that could get me locked up. As I looked at the incline of vertical rocks, I wanted to push the right one over and watch the pile topple in a chain reaction—like a row of dominoes in a time-wasting but addictive video. Then, the rocks morphed into a flight of stairs or an escalator I wanted to climb. Then, to my horror, I saw the shape of a man covered in a leafy shadow blanket lying face-down at the foot of the stairs. Has he fallen? Is he injured? The city should put up handrails for us to hold onto. It’s a lawsuit waiting to happen.

This week’s second image—One Among Many: A Golden Hour in the Granite Dells—isn’t nearly as complex. It’s only a round rock that climbed on top of a larger one to catch the last rays of the evening sun. That’s all there is. There’s nothing more or nothing less—except perhaps it’s a flattened bowling ball, deflated beach ball, or it could be an off-scale model of Yosemite’s Half Dome. I’m not sure—maybe the hot sun is getting to me.

Thanks for stopping by this week. I hope this week’s image and exploration of the photographic eye have piqued your interest. The world is full of wonders waiting to be captured by your lens, even in the most unexpected places like Arizona’s rebellious granite. If you’re brave enough to examine the dead body in “The Escalator Effect” (if you can find it), you’ll find larger versions on my website (Jim’s Website) and my page on Fine Art America (FAA Page). Join me next week for my final Granite Dells photo story. I’ll be back if I don’t get caught up in a butterfly net before then!

Till next time

jw

Techniques: Developing Your Photographic Eye

Back in the stone age, when attending night classes at Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design, I befriended a fellow student who was an exceptional photographer. We’d brainstorm ideas about our weekly assignments, spend time in the darkroom together, and learn techniques from one another. Vince’s work made everyone’s jaw drop when we sat for our professor’s weekly critiques. The instructor would allot ample time to hold up the photos Vince turned in as a shining beacon to which the rest of the class should aspire. Then he’d critique my work with, “That’s nice too,” before moving on to the students who need more help. Vince had the eye.

Since then, I’ve been part of many discussions centered on talent—either you got it, or you don’t was the consensus. Talent is innate and can’t be learned—to which I say rubbish. Talent isn’t a binary thing like a light switch—on or off. Like most traits in life, it’s a continuum, a line that everyone fits on. It’s easy for a select few, but we must work harder to grow.

There are helpful rules in photography that you have to learn, like beginners practicing scales on a piano. We’ve previously touched on some of those rules in this forum: framing and composition, the rule of thirds, manipulating the light, and so on. Understanding and following these rules doesn’t make our work great. Early in our careers, we work hard to master the rules so they become intrinsic, and we stop thinking about them while we’re shooting—like the musician who doesn’t need to look at the piano keys to play a tune. It’s then that your mind begins to see beyond the obvious. Instead of asking, “What should this tune sound like?” you can ask, “What should this tune feel like?” When you don’t think about the rules and trust your imagination, your work speaks with your voice. So, when I hear someone say they don’t have talent, I don’t believe them. Everyone has some talent; they have to decide if they’re willing to do the extra work—is the trade-off worth it?

It all begins with observing the world and finding what speaks to you. Whether it’s the rebellious charm of Arizona’s granite, the unexpected formations that emerge in the sunlight, or the whimsical ideas that come to mind when a rock resembles a flattened bowling ball, your unique vision will set your work apart. So take your camera, wander the trails, get lost if you must, and let your imagination guide you. Embrace the unexpected, and you might discover the extraordinary in the ordinary. Keep pushing, keep experimenting, and never doubt your ability to see the world in a way that’s uniquely yours.