Spring is ending and there are signs of its imminent demise everywhere. This year’s crop of quail chicks, which looked like gray dust bunnies a few weeks ago, has already grown to three-quarter size. I’ve seen normally wary jackrabbits come in off the desert looking for water. Tropical storm Bud managed to bring rain throughout the valley except at the airport where the Weather Service records official measurements. It brought a welcome break from the heat and an early arrival of the summer monsoon storms. As far as I’m concerned, summer started when the thermometer exceeded the century mark several weeks ago. The Summer Solstice is tomorrow—the official start of summer and the longest day of the year. You’d think that all this extra daylight would be better for picture-taking. Not in the Sonoran Desert—not for me.

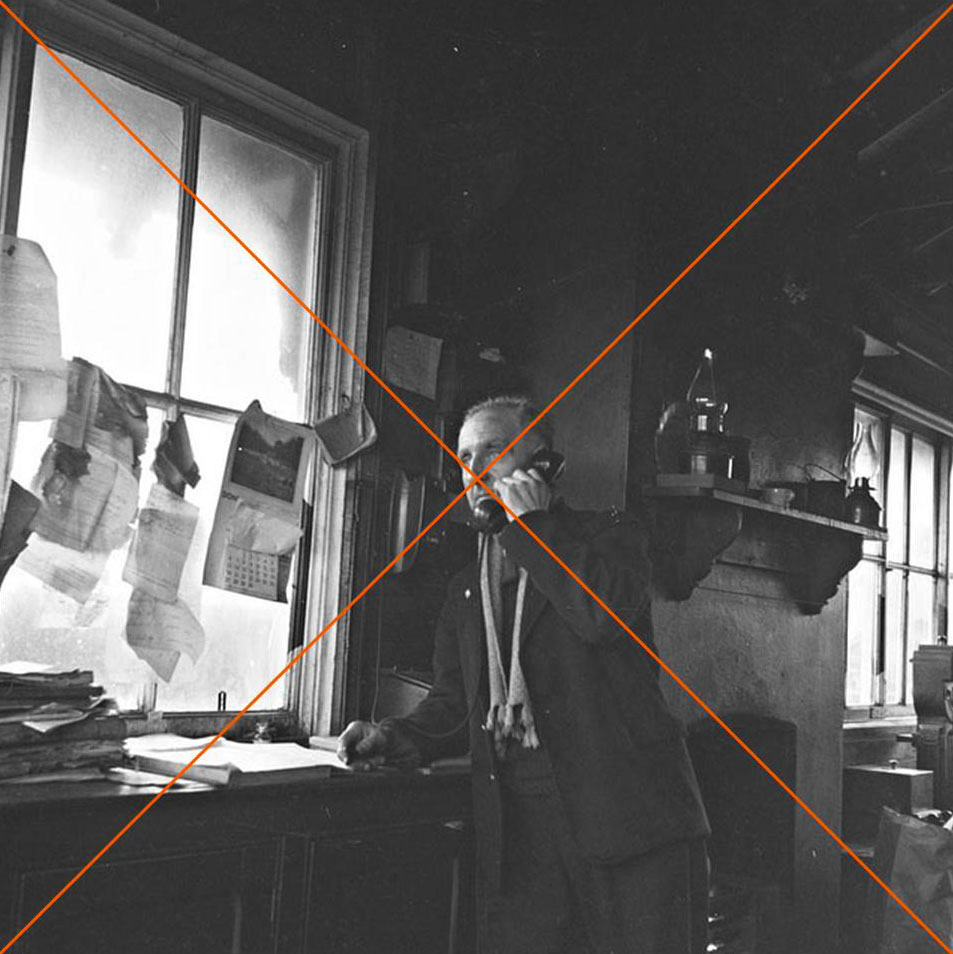

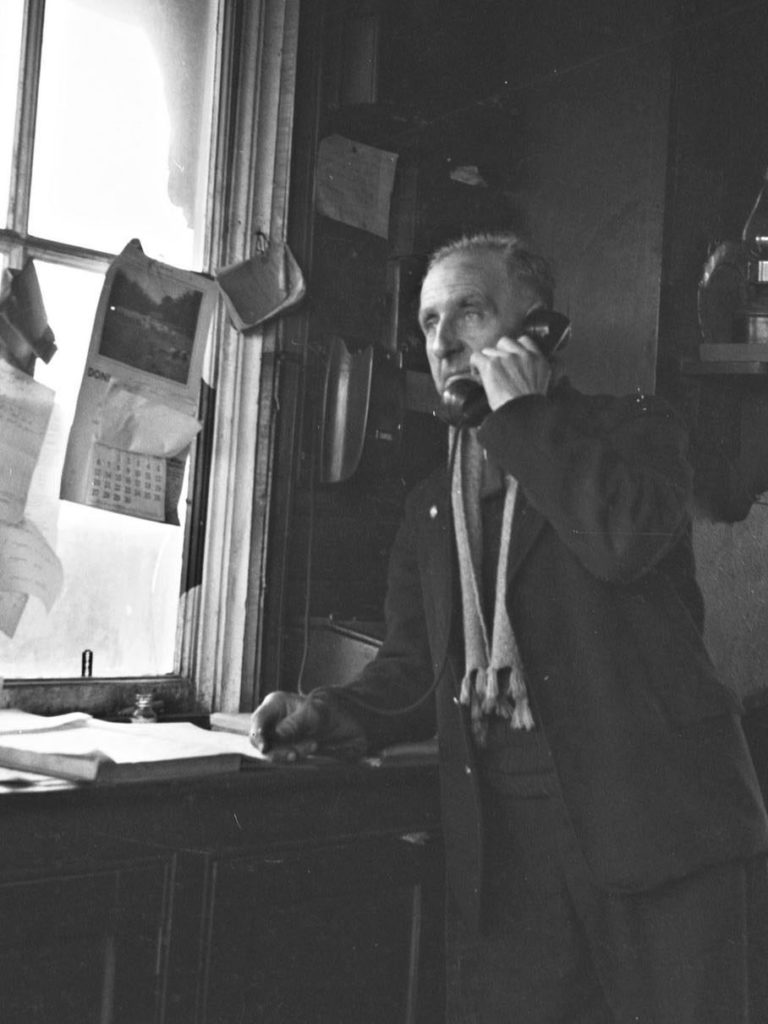

As an art-photographer, I consider myself average at best. The reason is partly that I’m not that creative and I’m too lazy to really work hard at it, and partly because I work too fast. I’m comfortable knowing this, but to compensate I use every advantage I can. I use high megapixel cameras so I have lots of margins when editing. I print on high-quality paper and mat to museum standards so my product has lasting value. I’m learning to make my own frames to differentiate them from cheap import stuff. And finally, I only shoot when the light is best—the Golden Hour or the Blue Hour—the short period before or after the sun transits the horizon. The rest of the time, the sun is over the yardarm—the term sailors on tall ships used when it was time to go below deck and drink rum. In photography, the light has lost color. The landscape goes flat, there’s too much contrast, and—especially in the desert—there’s too much glare. Photographers say, “We’ve lost the light.”

In the desert southwest, there are still periods when the light is pleasing in spring and summer, they’re just very short. I joke when I say, “morning’s golden hour lasts 5 minutes,” but I’m not far off. I don’t have the luxury of wandering around and shooting multiple subjects; I must plan and be there when the light is right. The reason for this phenomenon—here in the desert—is the sun’s angle. Because we’re so close to having the sun directly overhead this time of the year, the light comes straight through the atmosphere and that’s when the sun’s light is the whitest. The lack of humidity here plays havoc too. In the dry air, light reflects off objects which washes out the colors. Just wear a pair of polarized sunglasses to see what I mean.

This light thing doesn’t happen globally. I’ve read internet posts, written by northern photographers, longing for the long summer days and better light. The first time I noticed a difference was when Queen Anne and I visited New Zealand. As we explored the islands, we agreed on a schedule where I could shoot in the morning then travel to a new place where I could shoot again at day’s end. I kept messing up our plans because the light was still good and I was still working at 11:00 am; something I normally wouldn’t do. I had the point really hammered home to me a couple of years ago when we were traveling through Idaho. While there, I got up before sunrise to shoot a grain elevator and as I walked to the scene, I looked for the brightest part of the sky to guess where the sun would come up. It surprised me to find that the sun didn’t rise that day—at least vertically like I’m used to—instead it slid west along the horizon for several degrees before clearing some distant trees. The light on the grain elevator was a different angle than I expected and I had to move the camera to compensate. I got my shot went back to the trailer and, before 6:00 am, I crawled back in the sack. When we packed and left later that morning, we drove by that old building and the light was still good. I could have slept in, had a cup of coffee and still got my shot.

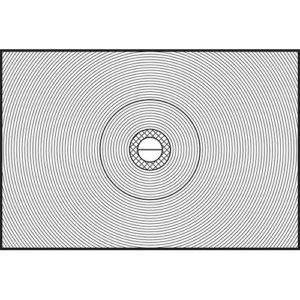

My argument can be condensed into this; the working length of good light changes with latitude during summer. It’s longer in the north and shorter here in the south (yes, in the southern hemisphere the water circles the toilet backward). It all has to do with the sun’s light angle through the atmosphere. Evidently, this isn’t a new idea because I found this neat sun-angle calculator on the Internet. It’s really slick. You put in the day and place, and the map will display the angle of sunrise and sunset. Then you can move the pointer north or south and watch as the angles change.

To get through this period of long (hot) days, I have a couple of strategies that get me by. I slow down my productivity. As I said, instead of wandering and looking for something to photograph, I’ll scout sites out. After finding a good subject, I’ll go back at a time when the light will be right. If I have all the details worked out, I’m out and back within an hour. You could call it, Hit and Run shooting. My favorite coping mechanism is to go where the light is better. If the light won’t come to you, then you go to the mountain. In Arizona, we have an old tribal word for such behavior—snowbird.

Until next time — jw