As an undergraduate in college, I signed up for a class in art history for three automatic credits. Many students complain that this required course is lame. Still, I must have accidentally learned something when I thought I was napping in the classroom because now and then, I’ll spot something on TV, and I get to turn to Queen Anne and spout some useless trivia to impress her—it doesn’t work, and I get the usual eye-roll. One of the things I wondered about in that class was why were so many of the Greek and Roman era statues damaged. Later, I found out that looters damaged them when they ripped the artwork from their pedestals. But I still wonder, “What happened to Venus de Milo’s arms, and where are those missing hands and feet?”

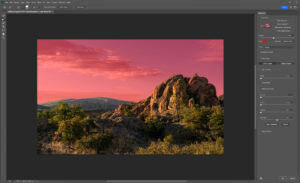

I may have found a partial answer, and it’s in the final image from our Granite Dells project. On my morning outing, when it wasn’t hot, and I had plenty of water, my brain was operating at its peak as I followed the well-worn trail before dawn. My primary focus was not falling, but that still left time for me to snap photos when I wasn’t moving. One of those shots is A New Day’s Glow at the Granite Dells—this week’s featured image. Like last week’s picture, I later saw things in this image that weren’t there when I was on the trail.

At first glance, the image may look like just another example of weathered granite in the Dells. But on closer inspection, it’s as if the place is a secret stash for all those missing statue appendages I wondered about in college. Along the ridge left of the center, there’s a right foot with two toes jutting into the air, obscured partially by the bush. To the right of the center, there’s a left foot, complete with a visible toenail on the big toe. The more you look, the more toes start appearing throughout the photo. Eureka! It’s like I’ve stumbled upon the lost’ foot locker’ of ancient art—a clandestine graveyard of dismembered statue feet! Perhaps they hide it under a blue tarp during the day; otherwise, it would have been discovered by now.

I’m not alone when I look at the Dells and see things that aren’t there. Another group of visionary men did the same thing over a century ago. They were farmers from Chino Valley and Prescott, looking for reliable water sources to irrigate their expanding agricultural lands. Ignoring the rugged beauty of the Granite Dells, they recognized an opportunity in the flow of Willow Creek and Granite Creek. In 1900, they constructed the first dam, damming Willow Creek and forming what is now known as Willow Lake. A few years later, in 1908, they dammed Granite Creek, creating Watson Lake. These manufactured reservoirs transformed the wasteland into valuable water storage and provided the area with dependable year-round water, fueling growth and prosperity. Today, the lakes and the surrounding Granite Dells continue to be a vital resource, offering a balance between human needs and natural beauty.

This week’s second photo shows Willow Lake waters lapping the Dells’s eastern shore. When the City of Prescott bought the lakes and surrounding land in 1997, they intended to preserve the area as a recreational preserve. And that’s how it worked out. Hikers, rock climbers, and old photographers use the dry sites, while other outdoor types like to get out on the water.

Granite Dells are more than just a collection of impressive rocks. Their charm lies in the subtle details and the stories they seem to tell. From imaginary toes to victory signs, from the gentle embrace of lichen to the lively dance of water plants, every visit unveils a new layer of beauty. We’re glad you joined us on the trails of Granite Dells, and we hope that you didn’t get frightened by the shape-shifting rocks. I have published two larger versions of this week’s image online, should you want to count the little piggies with roast beef. The first is on my Website (Jim’s web page), and the second is on my Fine Art America Page (FAA web page). I think it would be great to hear how many toes you found by leaving your count in the comments section below—of course, any snide remarks are welcome, too. We hope to see you back here next week when we begin a new project to get us through September—usually the last of our hot summer months.

Until next time

jw

Techniques: Playing with Reflections in Water

Capturing reflections in water can transform an ordinary photograph into a visually captivating image, providing a unique perspective and adding a sense of symmetry and depth. Whether it’s the clear reflection of a mountain in a calm lake or the distorted ripples of buildings in a bustling city canal, water reflections can be a photographer’s tool to create a sense of harmony and intrigue.

In this week’s second photo—Water and Rock: Evening at the Dells—the reflections in Willow Lake offer a mirror-like portrayal of the rock formations, doubling the visual impact and delivering a parallel world beneath the surface. These reflections emphasize the rock’s unique shapes and capture the colors and textures of the sky and landscape, enhancing the overall composition. Utilizing reflections requires keen observation and sometimes even waiting for the right moment when the wind calms and the water surface becomes still. Consider the angle of the light, the state of the water, and the composition to maximize the reflective effect. By experimenting with different perspectives and settings, reflections in water can become a decisive element in your photographic storytelling, elevating a simple scene into something extraordinary. Despite all that planning, sometimes you have to have dumb luck, as I did with this photo of the Ruby Range and Kluane Lake while on our 2016 Alaska adventure (see it here).